What do we make of the Nuggets?

People are talking about the Nuggets like they are a juggernaut, but are they? How far are they from everyone else?

Analytics are useful for two reasons: 1. they can help us more accurately and precisely describe things that have happened in the past and 2. By identifying trends in past data, they can help us predict things that may happen in the future when they fit into the trends. Basketball has one of the richest analytics landscapes of any major sport. It is not quite to the level baseball has reached where the game can be almost entirely described with a series of numbers to the point where the game borders on being played on calculators, but it still has an enormous wealth of data points we can comb through and identify trends.

There are bounds on what we expect and almost everything falls within those bounds; no post-merger team has won fewer than 10 games in an 82-game season and no team has won more than 73, net rating exists between -15.2 and +13.4, no team has lost less than 0% of their playoff games and no team has won more than 94.1%, and playoff net rating exists between -31.3 and 13.4. While there is no rule that says these numbers cannot be exceeded (except the 0% in the playoffs), no one would ever predict these records are broken. The reason for this is pretty straightforward, we understand that extreme outliers are generally the result of a very specific set of circumstances and if there was any reasonable likelihood of those circumstances being reproduced then these numbers would not be outliers.

Beyond bounds, we can also see incredibly persuasive trends in correlated data. For example, of the 47 teams to win a title since the merger, 43 of them have passed Phil Jackson’s famous 40/20 test. In the same sample, all but the 95 Rockets have been both a top 3 seed and had a top 10 net rating in the regular season. Of all these teams, almost ¾ had a starter that had previously won a ring, and all but the 77 Trailblazers, the first post-merger champion, had a rotation player (more than 90% of playoff games played, greater than 10 minutes per game) who had previously been to a conference final, and 83%, or about 5 in every 6, had a player who had already won an MVP on the roster. The best player on these teams had an average experience of 9 years in the league and the teams averaged 2 players who had or would make an All-NBA team within two years of the title. I could throw out more stats, but my point is that we have a ton of data that we can use to predict results in an NBA season and they rarely fail.

When we look at the Nuggets, I’ve had a lot of trouble figuring out exactly how to evaluate them. On the one hand, they check a lot of the boxes, and their championship last year could by no means be considered an outlier. They hit 40/20, secured the top seed in their conference, had the 6th best net rating in the league, had an MVP with 8 years of league experience, and a starter who had won a title in 2020. They only had 1 All-NBA player (unless Jamal Murray makes it in 2024-25), but that test is less dispositive and they checked every other box. It caught no one by surprise that they won the title.

On the other hand, they just as easily could have lost. The Celtics and Bucks also had top 3 seeds, top 10 net ratings, and met 40/20. The Celtics had neither an MVP nor a starter with a ring and their best player only had 6 years of NBA experience but they had 2 All-NBA players and plenty of deep playoff experience. The Bucks only had 1 All-NBA player, but he was an MVP with 10 years of league experience and several of their starters had rings. Perhaps that was enough to write the Celtics off, but the Bucks could just as easily have been the “no surprise they won the title” team of 2023 as the Nuggets.

That said, the Nuggets certainly outperformed their regular season in the playoffs. They had the 11th-best playoff win percentage and the 15th-best net rating of all post-merger champions. I’ll couch these numbers by pointing out they are top quarter and top third respectively (both fall within 1 standard deviation of the mean). But of all the teams who are top-15 in either, the Nuggets had the worst record and worst net rating. The question of whether or not a discrepancy exists is a matter of degree. There is a suggestion in this data that the Nuggets perform better in playoff scenarios than they do in the regular season and we should expect that to continue, but without more data, we can’t rule out that this was just normal variance. After all, the Bucks and Celtics both lost to a team that had outlier good shooting and saw their best players get hurt; the Nuggets easily could have seen victory come from outlier luck in the other direction.

Let’s start by qualifying the idea of a “playoff riser.” NBA fans love the idea of a player who seems to thrive under pressure and gets better in the hardest moments, but typically what we see in the best players is simply that they hold relatively steady, or see minor increases, despite the increased intensity. To illustrate this, we can look at two all-time greats. Michael Jordan in his 6 championships seasons averaged 30.5/6.2/4.8 with 3 stocks, 2.4 TOs, and slashing 50/35.2/82.7 during the regular season. In the playoffs, these became 32.6/6.2/5.4 with 2.7 stocks, 2.6 TOs, and slashing 47.8/33.8/82.7. What we’re generally seeing here is a higher offensive load being held and trading a little bit of production for a little bit of efficiency. He saw increases in scoring by about 7%, assists by about 12.5%, and turnovers by about 8%. Meanwhile, efficiency dropped by 4% in both field goals and 3-pointers.

Lebron James in the 8 consecutive years he went to the finals averaged 26.5/7.7/7.4 with 2.2 stocks, 2.8 TOs, and slashing 53.4/35.9/73.6 versus 28.8/9.1/6.9 with 2.8 stocks, 3.1 TOs, and slashing 50.5/33.8/74.3. Most notable here is that stocks are up more than 25%. Scoring, rebounding, and turnovers are also up by 9%, 18%, and 11% respectively while assists, field goals, and 3s are down 7%, 5%, and 6%. Once again, this looks a lot like handling the ball more, shouldering more scoring burden, and sacrificing a little efficiency. While stocks are an imperfect measure of defense, it is also interesting that that volume went up so dramatically when we might expect the defensive intensity to drop a little when the scoring burden increases. This is likely a testament to Lebron’s potentially 1-of-1 physical attributes, not least of which is his stamina.

Let’s compare this to Nikola Jokić last season. In the regular season, he averaged 24.5/11.8/9.8 with 2 stocks, 3.6 TOs, and slashing 63.2/38.2/82.2 while in the playoffs he averaged 30/13.5/9.5 with 2.1 stocks, 3.5 TOs, and slashing 54.8/46.1/79.9. Immediately apparent is his absolutely absurd 22.4% increase in scoring, likely attributable to the 20.7% increase in his 3-point percentage and increasing his FGA by almost 50%. For context, the largest scoring increase Jordan saw during his 6 championships was 14.4%. Lebron had one season where he jumped by 23.6%, but that was in 2018 when Kyrie had left and Kevin Love was largely hurt, leaving him to carry a much larger scoring load.

Make no mistake, these numbers are stunning. The question is, why? What changed? A quick glance at some metrics for Jokić shows that during the 2022-23 regular season, he took 1.6 very tightly contested, 8.7 tightly contested, 2 open, and 0.4 wide open 2s per game. For 3s, these numbers are 0, 0.3, 1.1, and 0.8. In the playoffs, he lept to 1.9 wide-open 3s while seeing small across-the-board increases on everything else. More notable perhaps, is that while he shot 37% on those wide-open 3s in the regular season, he shot 54% on them in the playoffs. Among players to play 65 games that season and shoot at least 1.5 3s per game, the 3 most effective wide-open shooters were Damion Lee at 50.9%, Joe Harris at 48.3%, and Jevon Carter at 47.8%. This number speaks incredibly powerfully in favor of the hypothesis that the Nuggets’ playoff performance last year was simply a high-end outcome on the variance scale rather than an expected increase based on players rising to the occasion.

However, I have trouble setting aside the nearly 150% increase in wide-open 3 volume. It’s possible this can be attributed to the increased reliance on Jamal Murray and Jokić in a 2-man game in tougher situations. While neither Jokić’s rollman frequency nor Jamal Murray’s ball handler frequency see substantial rises in the playoffs, they saw their minutes increase from around 33 to almost 40 apiece, increasing the time they share the floor and necessarily meaning they will be partners for this action at a higher rate rather than running it with other players as they do during the regular season. However, while Murray’s points per possession as a ball handler increased from 0.97, the 74th percentile, to 1.17, the 91st percentile, Jokić’s went from 1.37, the 91st percentile, to 1.26, the 84th percentile. This would give some indication that this action is inflating Jamal Murray’s numbers, but less answers what is inflating Jokić’s beyond simple variance.

For Jordan and Lebron I was able to use their entire primes but for Jokić this sample is obviously not yet available. That said, we can try looking at previous years to get a sense of what the causes might be. This project remains difficult since Jokić has played in 5 playoffs but one was the bubble and one was the COVID season, neither of which have similar conditions to regular basketball at all so I do not feel good trying to extrapolate from that data. This leaves only 2018-19 and 2021-22 as samples. 2018-19 was Jokić’s first season as an All-Star and All-NBA player and his first year making the playoffs. That regular season he averaged 20.1/10.8/7.3 on 51.1/30.7/82.1 with 2.1 stocks and 3.1 TOs. In the playoffs, those numbers became 25.1/13/8.4, 50.6/39.3/84.6, 2, and 2.6. Once again we see an outrageous increase in scoring, 24.9%, and an absurd jump in 3-point percentage. In 2021-22, Jokić’s second MVP season, he averaged 27.1/13.8/7.9 on 58.3/33.7/81 with 2.4 stocks and 3.8 TOs. In the playoffs, these became 31/13.2/5.8, 57.5/27.8/84.8 with 2.6 stocks and 4.8 TOs. While this also saw a solid leap in scoring, efficiency plummeted, turnovers spiked, and assists dropped 26.6%.

Across the board, we see Jokić take an increased volume in the playoffs. In fact, his usage has gone up at least 3 points every single season of his career. His percentage on 2s always seems to take a substantial hit while his percentage on 3s seems to go up. Interestingly, the one season in our sample where his 3s went down was the one playoff he had to play without Jamal Murray. While I do want to take the other two seasons with a grain of salt, Jokić’s 3s also got better in the bubble, with Murray, and dropped in 2021, without Murray. This may suggest that more than Jokić, the thing that has given the Nuggets success in the playoffs is Jamal Murray.

I’ll start by saying Jamal Murray confuses the hell out of me. By my eye test, he is a mediocre combo guard who can handle a relatively high volume but isn’t elite. His regular season numbers tell the same story. His playoff numbers are absurd. However, his sample is nearly nonexistent. He has played 3 total playoff runs in his career, one of which was in the bubble. Let’s run through the same metrics we’ve used with other players. In 2019, he went from 18.2/4.2/4.8, 43.7/36.7/84.8, 1.3, and 2.1 to 21.3/4.4/4.7, 42.5/33.7/90.3, 1.1 and 1.6. This is a fairly typical playoff run; a slight increase in volume and a slight decrease in efficiency. In 2020, he went from 18.5/4/4.8, 45.6/34.6/88.1, 1.4, and 2.2 to 26.5/5.7/7.1, 50.5/45.3/89.7, 1.2, and 2.8. I don’t need to remind people that the bubble was completely ridiculous and Jamal Murray was a big part of that. Perhaps this is the moment he unlocked his brain and was able to become an absurd riser under pressure, but it’s hard to reach that conclusion definitively given everything else memorable from the bubble. In 2021 and 2022 he was out with an ACL tear and in 2023 he went from 20/4/6.2, 45.4/39.8/83.3, 1.2, and 2.2 to 26.1/5.7/7.1, 47.3/39.6/92.6, 1.8 and 2.5. Once again, absurd. This is a scoring increase of 30.5% while actually getting more efficient, doubling his stocks, and increasing his other counting stats.

We’re left trying to figure out how to explain this. This is a completely unprecedented rise and it is completely unsatisfying to say he is simply rising to meet the occasion; no one does this to this extent, ever, not Jokić, not Lebron, not Jordan. On the other hand, it is also dissatisfying to say this is simply the result of variance and cannot be replicated without more exploration. Perhaps the best comparison is to Manu Ginobili. Ginobli was also a combo guard who benefitted from playing next to an MVP-level big. Looking at Ginobili’s stats in 2005, he went from 16/4.4/3.9, 47.1/37.6/80.3, 2, and 2.3 to 20.8/5.8/4.2, 50.7/43.8/79.5, 1.5, and 2.9. This was also a 30% increase in scoring on higher efficiency while increasing other counting stats. Also similar, this was Ginobili’s third playoff run. If we use this as the standard, it seems unlikely we should expect repetition from Murray. Ginobili would not crack 40% from 3 in the playoffs again until 2016 and would never see his points per game rise by more than 3 between the regular season and the playoffs again in his career. The Spurs would win 2 more championships during Ginobili’s tenure, 2007 and 2014, but his specific explosion would not be replicated.

A handful of other players come to mind when asking about second or third options who exploded in the playoffs, but none quite resemble the absurdity we see from Murray. Kyrie Irving spiked in 2016, but he then continued to be his playoff self the next year in the regular season. We did not see the same up-and-down trajectory we’re seeing from Murray. Jason Terry in 2011 didn’t see quite the same explosion in volume but saw a similar flair in efficiency increase. He was already in his 30s which would have led more people to believe this was variance than a true leap as well. He would also come back down to earth, never have another playoff run where he was within 3 points per game of his 2011 run, and in fact, every successive regular season would also be worse than his 2011 season.

While it does seem most likely that Jamal Murray’s explosion last season was largely a good but not great player having an extremely high-end variance outcome, I want to touch on his clutch stats before fully closing the door on this topic. In 2023, Jamal Murray shot 35.3% in the clutch. This is despite shooting 37.9% on 3s, meaning he shot a disgusting 32.1% on 2s. In that year, the Nuggets were 53-29 overall, 22-15 in clutch situations, and 31-14 in blowouts. They were much stronger in blowouts than in the clutch, which isn’t weird but does counter the narrative. This season, Murray performed far better in clutch situations, slashing 57.1/40/84.2. The Nuggets were 57-25 overall, 26-14 in the clutch, and 31-11 in blowouts. I will do more with the team's clutch numbers in a second, but I bring this up to illustrate Murray’s career is not necessarily just a player rising to the occasion every time, but a streaky player who is sometimes very hot at the exact right moment.

I feel comfortable after having combed through this data suggesting that some of the absurd numbers we saw last year and the slight increase in performance between the regular season and the playoffs for those Nuggets are the result of variance, but that still leaves two important questions: 1. How good are the Nuggets this year and 2. Do we believe they can win this title?

Having rejected the idea that the Nuggets are a unique phenomenon within history who will rise above and beyond the call of duty in every scenario, we are left looking at them based on their team numbers. I’ll start by emphasizing how difficult it is to win an NBA championship, let alone back-to-back. If you are favored to win each of your four match-ups at 90%, you have about a 66% chance to win the championship and a 43% chance to win back-to-back championships. If your individual odds are something more reasonable, say 65/35 in any given match-up, you have an 18% chance to win the title and a 3% chance to repeat.

Three teams have ever eclipsed a 90% win rate in the playoffs, and two of them would repeat. Four more teams would eclipse 85%, two of which would also win the next season. These numbers likely show that it is even harder to repeat than we might think; a 90% win rate in individual games would result in an even higher series win rate. Part of this effect might be “championship hangover” where it is simply difficult to stay in the mindset necessary to win a championship for that long and part of it might be that oftentimes championship teams lose pieces year-to-year and it is hard to find 1:1 replacements for key players.

With that in mind, 12 of the 47 teams to win championships had won the prior year. 3 of these teams were on their third consecutive year, leaving 9 distinct teams that were able to go back-to-back. These teams were the 87 and 88 Lakers, the 89 and 90 Pistons, the 91 to 93 Bulls, the 94 and 95 Rockets, the 96 through 98 Bulls, the 00 through 02 Lakers, the 09 and 10 Lakers, the 12 and 13 Heat, and the 17 and 18 Warriors. Bizarrely, from 1987 to 1998 no one won a single championship without going back-to-back. This would have gone until 2002 if not for the singular Spurs title in 99. After these 15 years of dominance by superteams, the league seemed to achieve a state of relative parity and only three teams have accomplished the feat in the following two decades.

Also of note is the composition of teams who have done so. Each of the teams since 2010 had 3 players who had made an All-NBA team and were currently All-Stars in their prime. Both teams also had two players capable of leading a Finals team independent of the partnership. The Heat had two players who led teams to championships without the help of the other while the Warriors only had one, but the other player was also an MVP and had the misfortune to play with Russell Westbrook during his prime. These teams were certifiable juggernauts who had other teams tanking simply because they could not fathom trying to contend while they were around.

Separate from these post-2010 teams, every back-to-back team has had multiple All-NBA players. Murray is not eligible this year, but even if you expanded to allow for players to make it outside a title year, Murray is unlikely to make a team any time soon. Another problem for the Nuggets is that 8 of these distinct pods saw at least one of the seasons win 60 games. This all points to the idea that the Nuggets are simply not dominant enough to win two titles in a row.

With that said, we still have to assess how good the Nuggets are this year. Your odds to win a second title in a row get higher the closer you get to it; they’ve done the hardest part, winning the first title and now we just need the odds they get the second one. For this, I will once again look at historic trends. They check 40/20, they are a top-3 seed and have the fourth-best net rating. They have an MVP with 9 years of NBA experience and now have multiple starters with rings. They still lack a second All-NBA talent, but again, that is not dispositive. The one note I’d make about this year versus last year is that Murray’s hot streak simulated a second All-NBA player in the playoffs and it is unlikely he will do it again, not because of a gambler’s fallacy but because it was extremely unlikely the first time and I would have given the same answer then.

In terms of their competition, we have the Celtics, Knicks, Bucks, Thunder, and Wolves as top seeds. The Bucks do not have a top-10 net rating and therefore cannot be considered a true contender. The Knicks failed to reach 40/20 and can be written off as a result. The Wolves lack experience; their star is in year four and have no one who has played a Conference Finals this decade. The Thunder have Gordon Hayward who has technically played in the Conference Finals before, but he isn’t really in the rotation. Also, they have an average age under 25, once again pushing them to anomaly territory.

The Celtics still lack an MVP (though maybe they can be treated as if they do for precedent purposes), but now have a starter with a ring and 2 All-NBA players. Their top player has 7 years of experience, a little short, but closer to the average than before. Given these precedents, it would be extremely unlikely for anyone except the Celtics or the Nuggets to win the championship.

The difficulty, however, is that just because a team is unlikely to win a championship does not mean they cannot knock you out on the way to their own demise. The numbers suggest that each of the Thunder and the Wolves are within striking distance of the Nuggets and a series with luck slanted slightly one way could do it. Additionally, the Thunder are 3-1 against the Nuggets this year, suggesting a decent advantage in the match-up. Even an outlier team like the Suns, Clippers, or Mavericks could conceivably knock out the Nuggets under the right conditions; the numbers suggest they are simply that close to mortal. To paraphrase a well-known quote, the Nuggets have to beat a good team every round after the first, a good team only has to beat them once.

There are two concepts that I’ve seen floated heavily as reasons the Nuggets should be trusted more than other teams in the playoffs: their clutch stats and their record in games where they shoot poorly from 3. Let’s begin with the clutch. The Nuggets are third in the league in clutch win percentage at 65%, a 53-win pace over the course of a season. They reached clutch time in 40 games this season. They also boasted a league-best 24.5 net rating in clutch minutes. They and the Mavericks are the only teams to be top-3 in both. The only problem is there isn’t a lot of evidence that this translates heavily into championships. Teams must certainly be competent in the clutch, but they do not have to be world-beaters. I’ve previously written a bit about clutch numbers in the context of the Celtics (here) but will be doing a deeper dive into it in this post.

In the play-by-play era, there have been 27 NBA champions. On average, these teams won 62.9% of clutch games, good for an average of 6th in the league, and had an average net rating of 8.4, on average the 8th best net rating. Even using medians to control for huge swings in the small sample that is clutch time, these numbers are 64, 4, 7.4, and 8. Only the 15 Warriors, 14 Spurs, 13 Heat, 11 Mavericks, and 09 Lakers have been top 3 in both win percentage and net rating, bizarrely all 5 coming in a 7-year stretch. If you expand to the top 5 in both you get to add 3 more teams, getting to 8 of 27 total. You also add the Celtics this year who are 4th in both win percentage and net rating. It is rather difficult to conclude that clutch numbers have any special predictive significance beyond their general correlation with better teams being better in the clutch.

For the many Celtics fans who may feel that this can’t be right given how the clutch has felt like the team’s Achilles heel the last several years, I’ll agree there are limits. Only one team has ever won the title with a negative clutch net rating in the regular season. There is evidence that a team needs to at least be semi-decent in the clutch in order to perform in the playoffs. However, it is not clear at all that a team needs to be better than decent, and most championship teams are at least a little worse in the clutch than in the regular season. Most of the time, we see these numbers trend toward average rather than further separating teams from the pack. As previously noted, title teams are almost always a top-3 seed and top-10 in net rating, 5/27 were outside the top-10 in clutch record and 10/27 were outside the top-10 in clutch net rating.

In fact, the reverse might be true. As established above, title teams are almost always a top 3 seed, but are top 3 in clutch records less than half the time. Net rating is also unpersuasive. 25 teams have held a clutch net rating of +20 or higher in the play-by-play era. Of these, only the 11 Mavericks and 13 Heat won the title. The 04 Lakers and the 16 Warriors managed to make the finals, 5 teams lost in the Conference finals, and a staggering 14/23 teams were eliminated by the end of the second round. The list of teams at the absolute top is a who’s who of the most disappointing playoff collapses in NBA history. The top 3 are the 09 Cavs, a 66-win, +9.6 team who lost in the conference finals, the 16 Warriors, who won 73 games and lost in the finals, and the 22 Suns, who dominated a regular season and then flamed out in humiliating fashion in the second round. Some of the highlights in the rest include the 67-win 07 Mavericks eliminated in the first round, the rest of the late 2000s Cavs who played amazingly in the regular season and then collapsed in the playoffs, and the 18 Rockets who missed 27 3s in a row. This pattern seems to suggest the success in clutch minutes is not actually the result of being “built different” or whatever other abstract concept, but actually the result of a lucky streak of variance that causes the rest of a team’s record to be overinflated.

In terms of changes from how the Nuggets play normally to how they play in the clutch, there are a few of note. Their pace increases and they go from the 26th-ranked pace to the 9th. They also shoot better; moving from the 8th ranked eFG% and 11th TS% to 2nd in both. They pass the ball more but also turn it over more, going from 9th to 5th in AST% but 9th to 18th ranked TO%, ultimately dropping their AST/TO ratio from 2nd to 9th. Finally, they are the best clutch rebounding team in the league, going from 6th in offensive rebounds, 15th in defensive, and 6th overall to 6th, 2nd, and 1st. I won’t bore you by going over how each of these looks historically, but I will note these all basically have no correlation to winning titles. The point I am reaching here is that teams will often play a little differently in the clutch than in the rest of the game, but it’s not clear that that matters substantially or is more predictive of playoff outcomes at all. I think it is fair to say being bad in the clutch usually bodes poorly for teams, but when you are comparing different strands of good we are mostly throwing darts at a spinning wheel.

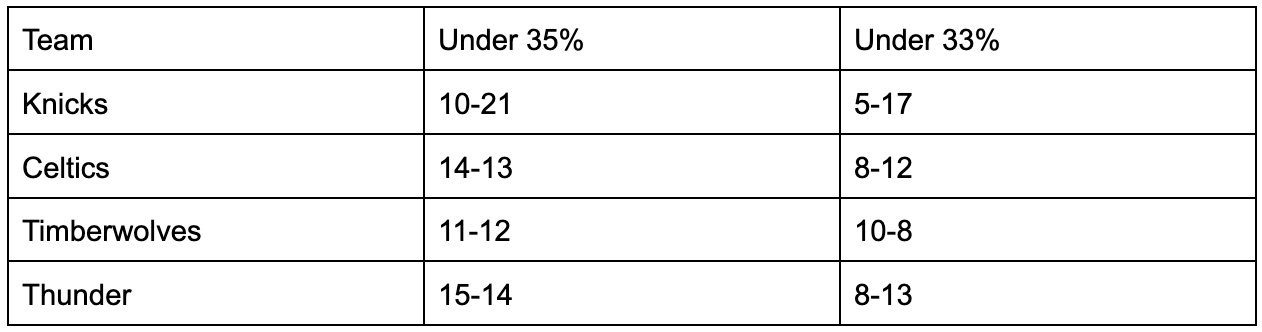

The other component is their ability to win without making 3s. The Nuggets played 32 games this year where they shot under 35% from 3. They were 18-14 in those games. However, if you drop this threshold to under 33%, they are 7-12. Compare these numbers to our other top-3 seed, top-10 net teams.

Interestingly, the Nuggets are the second worst of the 5 under 33%, notably the only team behind them is the Knicks, who are the only team here not to pass the 40/20 test as well. Second, they have the most games under 35%. Why does this matter? For one, the narrative that they have ways to win when their shot isn’t falling and other teams do not simply appears untrue. For two, having more poor shooting games negates this effect even if it were true. Let’s compare the Nuggets head-to-head with the Timberwolves here. We’ll be incredibly generous and only use the below 35% number. The Nuggets have a 56.5% win rate in these games, the Timberwolves have a 47.8. However, if we hold the teams’ win rate equal in the games they shoot above 35%, let’s say 75% for the sake of argument, we can see this impact. This is because 75% of 59 is 44.25, combined with their 11 wins under the mark, they have 55.25; in practice, 55. Meanwhile, for the Nuggets, 75% of 50 is 37.5, combined with their 18 under, is 55.5; in practice either 55 or 56. You end up with similar calculations for the Thunder and the Celtics, suggesting this isn’t actually reliably an advantage unless you can rely on both teams shooting poorly consistently.

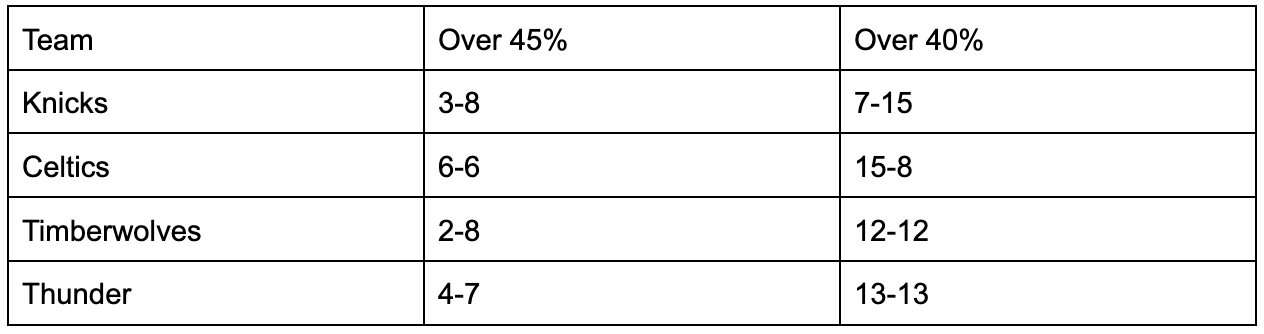

Conversely, the Nuggets are incredibly vulnerable to opponent’s 3-point shooting. They are 0-8 in games where teams shoot over 45% from 3 against them and 7-13 in games teams shoot over 40%. Comparing again to the above teams:

If we use a similar calculator to the previous set, assigning everyone a 75% win rate in games where opposing teams shoot worse than 40%, the records are Knicks 52-30, Celtics 59-23, Timberwolves 55.5-26.5, Thunder 55-27, and Nuggets 53.5-28.5. Once again, the Nuggets are the second from bottom, but this time the Knicks are much closer to them. What we are able to conclude here is the Nuggets are not actually less subject to the whims of 3s than other teams, what they gain from overcoming poor shooting they lose from being worse at shooting, and they are more vulnerable to other teams getting hot than all of our true contenders.

Coming back now to our earlier point about variance and even teams that are heavy favorites in each series still not having amazing title odds. The Nuggets, whose swings are more volatile than these other teams, are even more vulnerable to losing a series due to a slight change in look. Compounding this, they will likely have to defeat all three of the other 40/20 teams to win the title. The odds that one of these teams happens to be hot at the right team should feel insurmountable to most people. While the Lakers are a terrible shooting team and do not really have any way to get lucky and beat the Nuggets, anyone else could and therefore we should expect at least one of them to do so.

Before I write a conclusion, I’ll try one historical comparison that I think might be favorable to the Nuggets. The 95 Rockets were the worst title team of the modern era. They won 47 games and had a 2.2 net rating, good for a 6th seed in the Western Conference and the 11th-best net rating. They were also a repeat champion over a very middling 94 Rockets team, a 58-win 2 seed with the 6th-best net rating. By all accounts, they shouldn’t have had a chance, but they had Hakeem Olajuwon, probably the best player in the league at that moment, and maybe Jokić is too, perhaps these teams can be analogous.

The biggest difference is that the Rockets added Clyde Drexler, another All-NBA player, mid-season. While they only played at a 49-win pace with him in the regular season, they had a +13 net rating with him on the court. Reasonably, this might suggest that their regular season record was not reflective of the quality of the team that took the floor in the playoffs. The Nuggets don’t quite have any analogies to the Drexler acquisition, but they aren’t as bad on paper as the Rockets were. Perhaps the presence of a worse team on the back-to-back list makes it more reasonable to bet on the Nuggets, even if there is an intervening variable the Nuggets don’t have. The next worst back-to-back would be the 01 and 02 Lakers, but that feels like cheating since the 00 Lakers with the same core had already won the title and had all the normal regular season markers of a team that can go back-to-back. No other team has gone back-to-back without a 60-win team on one of the two legs and none of them have a second leg weaker than 56 wins (the 01 Lakers).

Quite frankly, the Nuggets would be the second most anomalous back-to-back winner ever, arguably even the first depending on how the Drexler trade was evaluated at the time. However, I’m not going to say the Nuggets won’t win this title. In a vacuum, they look like they have more title markers than any team except maybe the Celtics. The Celtics look better on some metrics - untouchable net rating and incredible record - but miss entirely on others; their star is still young and the roster doesn’t have an MVP (though perhaps it should). To count last year’s success against them this year might be to engage in some mild gambler’s fallacy (unless you believe in hangover) and if you don’t do that, they probably have at worst the second-best odds this year. Perhaps you can argue the league is incredibly weak right now based on traditional contention markers and the time is ripe for an anomaly. Maybe you can say that parity is at an all-time high and our historical trends aren’t useful in predicting this moment in time. But at the end of the day, I’m left concluding what I thought all along.

The Nuggets are good. They’re awesome. They are the best team in the West and I picked them to make the NBA finals. However, they are not a historic juggernaut. There are a lot of teams in the West who have very reasonable odds in a series against them and they will have to beat two of them just to make the Finals, and then a third to win it all. Their odds to make history go up each time they win a round, but right now The Field should be the overwhelming favorite. This isn’t a particularly interesting take; it is true the vast majority of the time, but the Nuggets have been treated all year as if they will simply coast to the finals and there isn’t a single statistical argument to support that. They will beat the Lakers in 4 or 5 games and then go through an absolute gauntlet the rest of the way. We can watch, we can cheer, they might win, they might lose, but the Nuggets are not gods and for the same reason I would never pick a team to win 71 games or have a +12 net rating, I cannot pick them to go back-to-back.